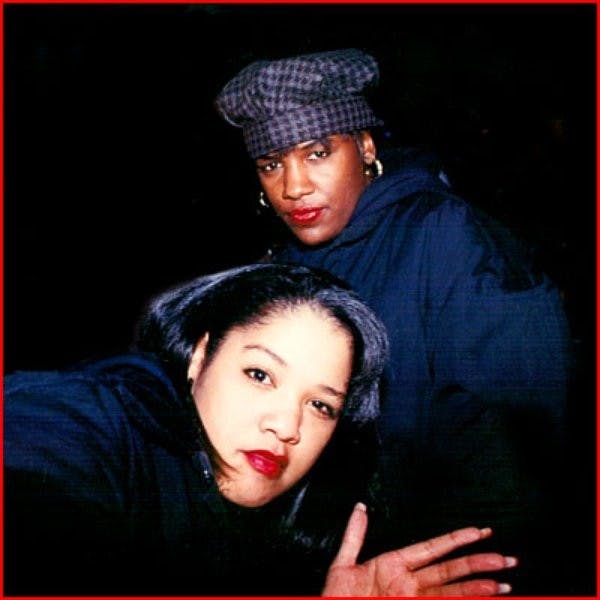

The Conscious Daughters: Beloved Bay Area Duo Repped For Realness

The Conscious Daughters: Beloved Bay Area Duo Repped For Realness

Published Tue, January 26, 2021 at 11:27 AM EST

Carla Green is happy.

Known to the rap world as CMG, one-half of Bay Area rap duo The Conscious Daughters, she smiles easily, jokes often, and doesn’t hesitate to announce that she feels “really good”. Since the pandemic, she’s been feeling “newly inspired,” which considering her track record, is a great thing.

In 1993, when Conscious Daughters dropped their debut Ear To The Streets, they were like a breath of fresh air, magnifying the sound that was brewing in the Bay Area. Bay Area rap was already bubbling, anchored by acts like Vallejo’s E-40 and The Click, and Oakland’s Too $hort, Paris and Digital Underground. But when The Conscious Daughters dropped, it hit a little differently: they were like the cousins you wanted to kick it with to seem cool, and maybe soak up some game.

The Conscious Daughters — Special One (Karryl Smith) and CMG— not only brought a female perspective, but raw energy that was infectious. CMG reasons that’s because everything about Conscious Daughters was authentic; they weren’t put together by some label executive. They’d been best friends since they were 11.

“We met through a mutual friend, and we both had similar backgrounds,” CMG says, adding that she grew between Berkley and the El Cerrito near Richmond. CMG, who is bi-racial (her mom is Native American and her dad is Black), says her parents were hippies, and that her dad was originally from Philadelphia and heavy in the music scene.

“One of his best friends eventually became the lead singer of the Temptations, Ron Tyson,” she says. “His other best friend was Frankie Beverly. When my dad came to California, the band Maze moved into our two-bedroom apartment, so I grew up a band baby.”

Meanwhile, over in Richmond, Special One also had a music background—her mom worked at the radio station, and by the time she was 13 she knew how to work all the equipment.

“We loved music, and we used to play music all day,” CMG remembers.

By the time the pair hit high school, their love for music was widely known. Special One took a radio class, but it didn’t last long because she “wowed” the teacher.

“She knew how to operate everything already!” CMG laughs. “He couldn’t teach her anything... so he made her the program director at the radio station all four years.”

Special One’s program director gig worked out for both of them. Together, they hosted radio shows and quickly made a name for themselves around town, even though it was only a 10-watt station.

“Everybody would tune into our shows,” CMG remembers. “Because of her connection to the radio station through her mom, we were getting tapes from New York— the Mr. Magic Show, and all that. We started playing that out here—they loved it. Also, Karryl was an all-star athlete. She was a basketball star, she’d be hitting 40 points a game. She was an all-star baseball player… she was probably the most popular person in the whole school, and she was my best friend.”

By the time they left high school, the duo was pretty popular around town. They’d started rapping and called themselves Chaos, freestyling on a whim at local clubs and recording songs. On the side, CMG went to computer school, eventually landing a job in software development.

“I ended up being involved on the original development team for Tetris,” CMG says, adding that she later worked at George Lucas and LucasFilms for five years.

But music was in her blood, and so she kept rapping and recording with Special One, a choice that paid off when the pair decided to attend a Digital Underground release party in San Francisco. By that time, they’d changed their name from Chaos to The Conscious Daughters, and when they ran into rapper Paris while rocking their own branded clothing, he was immediately intrigued. Paris had made a name for himself with his searing socio-political lyrics, making waves when his 1992 single “The Devil Made Me Do It” was banned from MTV.

“As soon as he saw ‘The Conscious Daughters’ he was like, ‘what are these girls about?’” CMG says. “So, he came over and introduced himself and said, ‘what is this conscious daughter stuff about?’ Karryl had this personality that was just bubbly. She was hilariously funny. She pulled our tape out, like ‘bam!’”

Paris took the tape and called them about a week later. He said he was leaving Tommy Boy and starting his own label, Scarface Records, and wanted them to join his roster.

“We had a meeting, and the rest is history,” CMG says.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

As soon as [Paris] saw [the name] ‘The Conscious Daughters’ he was like, ‘what are these girls about?’ So, he came over and introduced himself and said, ‘what is this conscious daughter stuff about?’ Karryl had this personality that was just bubbly. She was hilariously funny. She pulled our tape out, like ‘bam!’”

- C.M.G.

In 1993, The Conscious Daughters dropped their classic debut Ear to the Streets on Scarface/Priority Records.

“We didn’t expect anything from the album,” she admits. “We knew we had enough money to pay our rent, and that we were going on tour, and we were gonna be on TV, and those three things kept us smiling every night.”

Hard-hitting throughout (“TCD In The Front”), sometimes reflective (“Sticky Situation”), funny (“What’s A Girl To Do”), and full of feminine perspective that mingled with their unbridled energy, the album earned industry buzz and helped the Bay further ID its sound. Produced entirely by Paris, the lead single, “Somethin’ To Ride To (Fonky Expedition)” is now considered a rap classic, a blaring display of Special One and CMG’s natural chemistry as they ping pong over the slow-riding beat. Put simply—nobody sounded like them.

“It was so authentic and organic,” CMG says of the album. “I don’t think we knew that we were gonna blow up as big as we did.”

Paris not only handled all the album’s production, but he also was serious about the project’s tone.

“He loved the way we flowed, loved the way we related to the streets people accepted us... the guys loved us,” CMG says. “He wanted to send a message through us, so every album that we put out, he said, ‘I want to write a song.’ He wanted a message rap. We didn’t write message raps. We were drinking 40s and smoking weed. Every time he came into the studio, he would be annoyed, but he got used to it after a while.”

She laughs, adding that Paris was a good guy, and “really inspirational” to them both. Perhaps surprisingly, so were East Coast rap group Fu-Schnickens. CMG says that when they were out on the road touring, they studied them and the quirky, Staten Island-based UMCs to get an idea of how to handle themselves on stage.

“We learned how to work with each other on stage without being boring,” she says.

The album’s second single, “We Roll Deep” further solidified The Conscious Daughters as a fresh voice in hip-hop, and Ear To The Streets peaked at #126 on the Billboard 200 and #25 on the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart. The album became one of the early markers for the mainstream talent that would emerge from the Bay.

CMG, who didn’t ditch her tech gig until it was time to go on tour, says that when it came time to record their second album, 1996’s Gamers, they were more focused than ever.

“We knew we wanted to write and deliver,” she says, adding that while they wrote all of their lyrics on the first album, Paris would come in and occasionally tweak bars here and there. “We were really pleased with it.”

We learned how to work with each other on stage without being boring."

- C.M.G.

For Gamers, they branched out with their production. Sam Bostic (E-40) and Rick Rock (Snoop Dogg, Method Man, Xzibit, Fabolous) among others offering production, while longtime friends Suga T and Mystic, along with Bay Area rappers Mac Mall and Money B offered assists.

"They were dope," Money B says. "They were innovators, especially coming out of the Bay Area. Mad respect—musically and lyrically, they had it. Even outside of music, we are friends."

The most notable track on the album is the grinding, funky “Gamers,” which was also the lead single. Other standouts were “You Want Me” and “Come Smooth, Come Rude.” But while Gamers was a solid offering from a group that seemed to have a lot more left in them, by the time 1997 rolled around, things spiraled quickly. And in the early 2000s, the file sharing service Napster entered the game, and the music industry was flipped on its head.

“When Napster came out, that’s kind of when everything fell,” CMG remembers, admitting that she wasn’t immune to new download access, and still has a computer full of classics herself. “When the industry fell, when people started closing their companies, they started merging. Everybody got dropped from Priority and we just never really recovered from it.”

TCD recorded another album, The Nutcracker Suite, in 2009 and CMG released a solo project in 2011, The Jane of All Trades, which she says did well for her financially, although neither project reached the success of Ear To The Streets or Gamers. Still, CMG has no regrets. Well, except passing on buying stock at the tech company she worked for in the early 90s which she estimates is now worth millions, and that they weren’t invited to be on Luniz classic “I Got Five On It” remix.

They were dope. They were innovators, especially coming out of the Bay Area. Mad respect—musically and lyrically, they had it. Even outside of music, we are friends."

- - Money B

“We should’ve been on that remix!” she laughs. “I think we were out of the country touring at the time, but I would’ve flown back to get on that.”

Remix appearance or not, she knows her place in the game, and the contribution TCD made to rap’s lexicon, and she’s happy when the contributions she and Special One, who unexpectedly passed away in 2011 due to complications from blood clots reaching her lungs, are recognized. She says Smith will always be remembered as a talent, an infectious personality who lit up every space she was in.

"I had a personal relationship with Carla and Karryl," Money B shares. "If I had a birthday party or something for my son, Carla would come through. And Special One, we used to see each other in the streets and at parties. She was a real one! [laughs] Talkin' about some gangsta shit, we got stories!"

"They represented for the Bay Area and I feel like that voice hadn't been heard yet."

“We had chemistry that was hard to create,” she says. “I could finish her sentence, she could finish my sentence and I think that really set us apart. Karryl was very unpredictable and very funny.”

Now, CMG is focusing her talents behind the scenes, with her label Faime, comforted by her contributions not just to the Bay, but hip-hop.

“I’m finally comfortable now with saying I’m a legend, even though I don’t think we made it as far as we should’ve in our career,” she says. “We didn’t have to sell our bodies. We weren’t rapping with our boobs out. We weren’t sleeping with our producers—even though there were one or two of them that I would’ve.”

She laughs, and in that moment, it’s clear what The Conscious Daughters brought to rap music—honesty, authenticity, and a presence that hasn’t been duplicated since.

“We didn’t do it for the fame,” she says. “It came out of a space of love. Rapping is pretty easy when you think about it. But when you have that special love? It makes you stand out from the crowd.”