Whereas early rap records were an attempt to distract from the ills of New York City, Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five’s “The Message” opened the aperture on societal woes like poverty, urban blight, and addiction.

Despite the personal nature of the song — as passionately delivered by Melle Mel — the song was written by Duke Bootee (Ed Fletcher) and delivered to the group’s record label for consideration.

The group’s reception was lukewarm at best, especially because the biggest song of the year was Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force’s “Planet Rock” which was an otherworldly sounding party record that combined escapism and futurism.

Many MC’s subsequently used a similar Gonzo-esque approach as Melle Mel did on “The Message”— crafting grim, first-person narratives – relating to the violence and drugs that continued to plague Black and brown communities.

In the 1990’s, a perspective shift occurred — finding the MC evolve from that of the all-seeing orator of criminality, to the perpetrator (coke rap). As a result, rap became participatory.

One of the criticisms of contemporary Hip-Hop is that the active participant in criminal culture is both the perpetrator and consumer of drug culture. Whereas The Notorious B.I.G.’s fourth “Crack Commandment” told listeners, “Never get high on your own supply,” it seems that now the rule is simply unwritten.

The effects of lean, opioid addiction, and cocaine have claimed the lives of prominent artists like DJ Screw, Pimp C, Juice WRLD, Fredo Santana, Mac Miller, A$AP Yams, and others. One could make the argument that because songs featuring mentions of lean, Xanax, and molly, often climbed the Billboard charts, that validation prompted a deeper fall into addiction. The higher the artists got, the higher their chart position.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

Consider four artists and their song titles: Three 6 Mafia (“Sippin on Some Sizzurp”), Future (“Dirty Sprite”), Young Thug (“2 Cups Stuffed”), and Lil Wayne (“I Feel Like Dying”). The titles go from the macro (the what), to the micro (recipe-specific), to over indulgence, and finally, to remorse.

The mention of lean, a cocktail of promethazine and a host of other sweetening substances like soda or candy, is hardly a shocking topic to hear about in contemporary Hip-Hop. Not only does it satisfy the raw reporting of songs from yesteryear, but it also implies a vulnerability that past artists once looked to completely avoid. By telling their fan base that he/she has shortcomings, it ironically gave them an even bigger profile.

I wanted to understand where this came from. While some people would point to the chopped and screwed mixtapes of Houston’s DJ Screw as the catalyst, I knew that the phenomenon of mentioning illicit drinks in music had to predate Hip-Hop.

In 1930, the nation was still in the throes of Prohibition, and many drinkers got their “liquor” — via a workaround — from patent medicines or extracts that were mostly alcohol. A favorite was Jamaican ginger extract, familiarly known as “Jake,” which was 70 percent to 80 percent alcohol, and sold for 35 cents a bottle.

When people got a taste for the remedy, the government told the makers that they had to make it less palatable. Some companies got creative, adding ingredients such as castor oil, molasses, glycine, and pine resins, and by increasing the amount of ginger in an effort to make it taste more like medicine, and less like a beverage.

One company experimented further, adding a chemical called ortho-tricresyl phosphate, or TOCP, a common ingredient in engine oils, that was tasteless and odorless.

The associated illness related to Jake occurred principally in the Southeast, south of the Mason-Dixon line, and east of, and including, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas, and Texas. Patients complained of pain and problems with their spinal cord and peripheral nervous tissue.

A front-page article published on March 7, 1930, in The Oklahoman described the symptoms and the probable cause: “Spinal afflictions, believed the result of poison whiskey, which has afflicted 60 men in Oklahoma City in the last ten days, and possibly caused one death, Thursday night brought an order from city officials for an investigation seeking the source of the poison liquor supply.”

The most notable effect became known as “Jake leg,” which was sometimes temporary, and sometimes permanent.

In Towanda, Kansas, one sufferer of Jake leg, dangled his legs in a smelly, oil-rich, slush pond and claimed great relief. Soon, there was a line of victims dangling their feet in the mess.

Another remedy came in the form of a superintendent of a Wichita farm who hooked a ball and chain to two men’s legs and had them hoe potatoes. After 30 days, they were “recovered from the dread disease,” according to the superintendent.

For those less fortunate, makeshift communities — not unlike Leper colonies — sprung up. In Wichita, this was referred to as “Jaketown.” At its height, 52 men lived there.

By 1930, the US government finally made a link between the Jamaican ginger and the symptoms. But according to the Johnson City Press, “…50,000-100,000 men were partially crippled with paralysis from the drink.”

Music has always been a vehicle to make sense of the world. Not surprisingly, singers latched onto the plight of the sufferers.

The first person to record a connection between Jake and the paralysis was Tommy Johnson who recorded “Alcohol and Jake Blues” in 1929. Between 1929 and 1937, other titles included “Jake Walk Blues,” “Jake Liquor Blues,” “Jake Leg Wobble,” “Jake Leg Rag,” “The Jake Leg Clues, “Got That Jake Leg Too,” and “Jake Walk Papa.”

Johnson bemoans on "Alcohol and Jake Blues,: “I drink so much of Jake, till it done give me the limber leg.”

On 1931’s “Bay Rum Blues,” Dave McCarn and Howard Long acknowledged their fear of Jake, singing, “Our Uncle Sam has taken our liquor away from us, when we make home brew he raises an awful fuss, we’re all afraid of ginger (jake) but we’ll drunk bay rum or bust.”

The effects of Prohibition could be seen and heard during the birth of the Jazz Age — aided by the clandestine nature of the speakeasies — where taboo song and libations could intermingle.

In 1929, Louis Armstrong’s recorded “Knockin’ a Jug” with Jack Teagarden. The song is considered one of the first documented collaborations between Black and white musicians.

In a country music context, there are more songs about drinking and drugs that can be properly counted. One could make the case that these topics are as fundamental to the genre as other human emotions like love, lust, and loss.

Certainly not all contemporary Hip-Hop boasts about drug culture. That’s a fact. But I had to consider the fact that because drug culture and usage are prevalent, there might be something else at play. Is "addiction rap" simply a symptom, and not necessarily the diagnosis of what plagues contemporary Hip-Hop? Perhaps science can help us.

In 1907 the American psychologist Frederick L. Wells (1907) first observed a remarkable phenomenon: When people see just one positive trait in another person (for instance, attractiveness or friendliness), their assessment of the person would be positive—even though that type of snap judgment could hardly be reliable. Psychologist Edward Thorndike backed it up with empirical evidence and coined the phenomenon as “the halo effect.” He described it as the cognitive bias whereby people would rate others favorably or unfavorably, based on one aspect of their leadership, looks, or character, without sufficient background information.

Conversely, there is a reverse halo effect, also known as the horns effect— a cognitive bias where a negative first impression of a person often results in a negative perception of them. For instance, the horn effect may cause us to stereotype a poorly dressed person as unreliable, although there is no evidence to indicate that reliability is tied to appearance.

Now, combine the horn effect with the writing of drug culture-promoting lyrics and you have a recipe to make a certain audience (of classic Hip-Hop) believe that the song was created without effort.

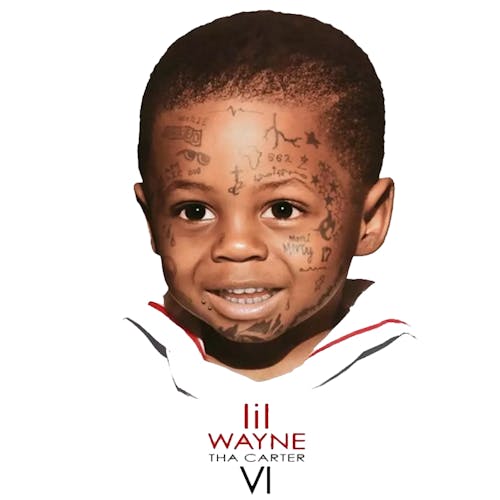

Many of today’s biggest stars like Jay-Z, Lil Wayne, Future, and Young Thug have all boasted about making music without writing down lyrics. Building upon this, newer artists tend to use a “punch in” method when recording — with ProTools serving as the pen and paper.

As Juice WRLD stated, “It’s like freehand versus tracing.”

As newer artists explore the potentials of an empty beat — perhaps aided by drugs and alcohol — the music tends to feel equally improvisational.

As the epigram tells us “If I don’t practice for one day, I know it; two days, the critics know it; three days, the world knows it.” The rejection, perhaps, of contemporary Hip-Hop is less about the subject matter, and more about how the music is made. Sometimes under the influence, often times unprepared, and often vulnerable, new Hip-Hop sends a new message: "But now your eyes sing the sad, sad song, of how you lived so fast, and died so young.”