Sustaining Hip-Hop Stardom Behind Bars

Sustaining Hip-Hop Stardom Behind Bars

Published Thu, September 17, 2020 at 8:09 PM EDT

There is no ending of media fixation on Hip-Hop and crime. Rappers’ run-ins with the law can make for water cool conversation or major backlash, but how rappers have creatively navigated the reality of a prison stint is a fascinating look at Hip-Hop history and how legal issues have re-shaped the careers of some of rap’s most iconic artists. Today, a rapper doing time is almost a non-factor in their career, as everyone from Kevin Gates to Kodak Black has been able to sustain a fanbase while doing serious time. But nothing is guaranteed when prison is involved; as rappers sustaining careers from behind bars has a varied history.

Recently, the ongoing drama surrounding former No Limit Records star Corey "C-Murder" Miller's stint in prison was again under the glare of the spotlight. Miller's conviction in the 2002 shooting of a 16-year old in Harvey, Louisiana has long been disputed; with celebs like Kim Kardashian and Miller's ex-girlfriend, R&B star Monica, taking up his cause. Miller was out on bond for an attempted murder charge in Baton Rogue when the Harvey shooting happened, and witnesses claimed they’d seen Miller with a weapon. But his brother, No Limit Records mogul Master P, took up his brother’s cause; as evidence suggested there were discrepancies. “My brother is no angel and has done a lot of dumb stuff like most,” Master P wrote on Instagram in 2018. “But I love him and I will fight for him to bring awareness to this injustice. You can’t choose your family but you can choose your friends.”

C-Murder would release albums like The Truest Shit I Ever Said and Screaming 4 Vengeance while serving out his life sentence (he’d record during visiting hours using handheld recorders), but the projects weren’t especially well-received and headlines became more preoccupied with C-Murder’s flailing relationship with his brother Master P than any new music from the convicted rapper. In 2018, a pair of eyewitnesses would recant their statements regarding the shooting, but Miller was not granted a retrial, as the judge ruled that the recantations “ did not meet the burden of proof for post-conviction relief.”

With stars from Meek Mill to A$AP Rocky having faced high-profile stints behind bars, and watching the way their fanbases and Hip-Hop artists and media have rallied around these artists, it’s clear that there is considerable power to mobilize both as a community and as an industry.

Photo by Skip Bolen/WireImage/Photo by Al Pereira/Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives

But a prison sentence meant something entirely different for a platinum-selling rapper at the dawn of the 1990s.

When Slick Rick pleaded guilty to attempted murder in 1991, he became the first major Hip-Hop artist to face serious prison time at the height of his career. Rick’s departure was swift: he rush-recorded 1991s The Ruler's Back, his follow-up to his platinum-selling debut Great Adventures Of Slick Rick, just before he was sentenced. Rick began serving his time, and there weren't a lot of “Free Slick Rick” shout-outs on records or in interviews.

But Rick was sustaining his career even in prison. He recorded a handful of tracks while out on a work furlough in 1994, and those songs became his third album, the appropriately-titled Behind Bars. Featuring production from luminaries such as Easy Moe Bee, a remix by Jermaine Dupri and then red-hot Warren G on the hit title track, the album showed that Rick was still inspired, creative and supremely talented, but despite the lead single’s heavy airplay on Rap City, the album didn’t make much noise in the mid-1990s rap landscape.

Regardless, Rick’s output while in prison was strong considering the limitations for such things in the 1990s. He recorded not only his own material, but guest spots with artists like Aaliyah and Montell Jordan. It helped set the table for his most fully-formed 90s album, 1999s The Art of Storytelling, released after Rick was out of prison and his first proper follow-up to 1988s Great Adventures..., the album that made him a star.

Rick somehow managed to navigate being a rap star behind bars at a time when that was the death knell of a career, but 2Pac’s 1995 incarceration for sexual assault happened when he was literally becoming the most talked-about artist in Hip-Hop. And dropping his seminal third album Me Against the World just after he’d begun his sentence at Clinton Correctional facility in upstate New York made Pac the first artist to have a Billboard album hit No. 1 while they were in prison. Obviously, 2Pac’s eight-month stint was unlike Rick’s six years, but these two high-profile incidents provide a bit of history for how rappers navigated recording and releasing music in the pre-internet days.

Wu-Tang Clan’s most idiosyncratic personality, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was sent to prison in 2001 after pleading guilty to cocaine possession. This particular verdict stemmed from an incident in when police found crack cocaine and marijuana on the rapper during a traffic stop. He avoided additional time related to his escape from a rehab facility and evading authorities for the beter part of two months before he was arrested in a Philadelphia parking lot.

Dirty’s legal troubles famously derailed his recording career: Elektra released the compilation The Trials and Tribulations of Russell Jones without his input and that released served as the fulfillment of his contract with that label. After Dirty’s untimely death in 2004, an album called A Son Unique was ultimately shelved.

Remy Ma was just breaking through as a major artist in 2008 when she was convicted of assault in a shooting of her former friend. She would serve six years of an eight year prison sentence, and during those years, Remy sustained some semblance of visibility via mixtapes The BX Files, Shesus Khryst and Blasremy. But her profile was immediately raised post-prison when she and her husband, rapper Papoose, joined the cast of VH1’s hit reality series Love & Hip-Hop. Like Gucci, Remy became arguably a bigger star post-prison than she had been before, and returned to the charts (and garnered a Grammy nod) with the Fat Joe collaboration “All the Way Up.”

And with her raised profile, Remy took up the fight for women’s prison reform.

"People whose husbands forgot about them, boyfriends forgot about them. Friends forgot about them," Remy explained to The Fader in 2016. "Their children forgot about them. We just get thrown away and I’m tired of it."

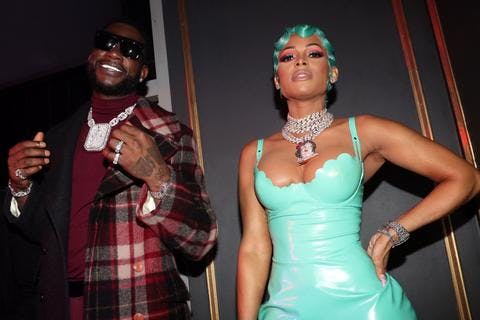

Photo by Shareif Ziyadat/FilmMagic/Photo by Johnny Nunez/WireImage)

Unlike the 1990s or even early 00s, it soon became apparent that, in the social media era, stars had a very different set of circumstances under which to operate should they wind up in correctional institutions.

Gucci Mane spent a great deal of his mid-2000s/early 2010s heyday battling a seemingly-unending string of legal issues: he’d faced a murder charge around the same time his debut album Trap House was released in 2005. Just as those charges were dropped, he was in county jail on an aggravated assault charge. In 2011, the rapper was recommended to psychiatric care at the behest of a judge, after Gucci was driving erratically in Atlanta. Two more assault charges followed that year, and in 2014, Gucci was sentenced to two years in prison after he pleaded guilty to possession of a firearm by a felon. Throughout his legal troubles, Gucci Mane maintained a constant presence; with a steady stream of mixtapes and albums like The Appeal: Georgia’s Most Wanted and The Return of Mr. Zone 6.

By the time of Gucci’s release in fall 2016, the trap legend had become one of the most mythologized stars in contemporary rap. He was welcomed back to the game with a lavish “Gucci & Friends" concert in Atlanta, and he came home to a largely unforeseen second act: his mainstream appeal was more evident than ever, he’d slimmed down his famously pot-bellied physique and he was profiled everywhere from The New York Times to Rolling Stone to VOGUE.

“Every single time that he was about to break through is exactly when he went back to jail,” manager Todd Moscowitz told The Times shortly after Gucci’s 2016 release. “Each and every time.”

Since that two-year prison stint, Gucci Mane has become the poster boy for Hip-Hop resilience and second acts.

In 2010, Lil Wayne was already a pop megastar. The Cash Money rapper was sentenced that year in prison after pleading guilty to felony gun possession in New York City. After his February is sentencing is delayed (Wayne famously posted: “I’m out this bitch! To all my fans, my real fans I really, really truly love you. I love you with all of me for real.”) until March, when he begins his term. Wayne stays connected via phone calls to DJ Scoob Doo, Funkmaster Flex, and MTV; as well as via his WeezyThanxYou website.

Wayne’s quasi-rock album Rebirth, dropped just before his sentencing, and while he was in prison, Wayne dropped the previously-recorded I Am Not A Human Being. The project debuted at No. 2 on Billboard the week of its release.

Max B has been incarcerated since 2009, but the New York rapper and Dipset affiliate has maintained a strong cult following in Hip-Hop—particularly amongst East Coast rap fans, but not exclusively: he was famously shouted out on Kanye West’s The Life Of Pablo and Wiz Khalifa name-dropped Max for years. Max B, born Charley Wingate, was sentenced to 75 years in prison back in 2009, charged as an accomplice to a robbery in New Jersey that left a man dead. He was later re-sentenced to 20 years after he pleaded guilty to aggravated manslaughter as part of a plea deal.

Max released music ranging from 2011’s Vigilante Season to the French Montana-assisted single “Hold On” last year. His reputation has only grown while he’s been imprisoned, another example of how incarceration isn’t the unsurmountable hurdle for an artists’ career that it may have been decades ago.

The recorded output of contemporary incarcerated artists may vary, but the common thread is an ability to sustain their careers despite losing their freedom. When looking back at earlier examples like Slick Rick, 2Pac, C-Murder and Ol’ Dirty Bastard, it’s hard not to ponder how things could have gone if the timing was different. Prison has never been able to hold the art of Hip-Hop’s greats, and nowadays that’s more true than ever.

*HEADER CREDIT: American rapper and producer Ol' Dirty Bastard aka Russell Jones (1968 - 2004) in a mug shot, US, 21st December 2001. (Photo by Kypros/Getty Images)