As hard as it is to believe, there was a time when no radio station would touch a Hip-Hop record. DJ's certainly had an inkling to feed the streets what they were purchasing, but program directors weren't having it. When there was the rare compromise, Hip-Hop was played only late at night when executives assumed people would be asleep. And then....something magical happened in Los Angeles, which gave legitimacy to the New York-born culture. The credit goes to one man.

Greg Mack, as he became known to millions of people around Los Angeles, had an inauspicious start. When he was a born in Emory, Texas, the midwife accidentally wrote "Macmillion" on the birth certificate (his government named should have been Macmillan). The mistake was a story that he grew up with. Like most rebellious teenagers, he attempted to forge his own identity — aided by the usage of mispelling. He felt like "Macmillion" spoke to his desire to make it big some day.

Texas was a far-cry from Los Angeles in the 1960s. Most schools were still segregated by race, and Black people could only check out books in dedicated branches — and only if a white librarian approved of what they were borrowing.

Mack spent his early years with his maternal grandparents, Hannah Bell McMillan and Neelan McMillan, and his mother, Willie Grace McMillan, in rural East Texas, where the family worked as tenant farmers growing cotton and raising livestock. His earliest childhood memory was watching a Ford Mustang drive by the family house in Emory, and watching TV shows like s Ironside and Marcus Welby, M.D.

When Mack was thirteen years old, his parents moved to Los Angeles. He remained in Van Alstyne, before moving to San Antonio where he lived with an aunt and uncle, and attended Fox Technical High School. One of the perks of his new school was the ability to intern in a professional setting instead of attending classes. Mack said he tried to secure placement in a law firm or doctor's office, but they were all full. The only thing left was at a radio station, KTSA AM 550.

"They were number one in San Antonio at the time," Mack told The Soren Baker Show. "The guy who taught me all of the tricks was named Robert Lopez, and I was his intern."

When there was breaking news — like when Elvis Presley died — Mack would bring his tape recorder onto the streets and get people's reactions. Other times, he'd answer the request lines. The latter, helped him earn favor with the ladies, who were calling in to the Top 40 radio format. Finally still, Mack was the station mascot — complete with a custom-fitted bird costume.

Lee Daniels, KTSA's program director, served as Mack's first mentor. He eventually offered him a full-time job. But when Daniels moved to Corpus Christi — after a fall out from a poorly executed contest that cost the station $50,000 — everything changed when the new boss arrived.

"I know that they like you," the new programmer told Mack. "But I'm gonna do everything I can to get your n****r ass out of here."

Mack cites this exchange as his first up-close experience with overt racism. He was 16 years old at the time. When he called Daniels, he was offered a weekend shift in Corpus Christi on the radio, and later got a gig as a VTR operator on television station where he was in charge of making sure the commercials aired correctly.

"When you're starting out like that, you still barely make enough money to get a pack of bologna and a loaf of bread."

- Greg Mack

Mack's stay in Corpus Christi was short-lived. When his fiancee, Cynthia, left him and relocated to Houston, he knew his only chance of salvaging the relationship was if he followed her there. He was able to land a job at KMJQ "Magic 102," which was his first stop at a station dedicated to "urban" programming. He was so well-received in his 6-10 PM slot, that according to Mack, rival competitors were offering up money to get him out of town.

Mack had a knack for research. He would call record stores and see what was selling, while also talking directly to the record companies to find out what they were pushing. He found that what was getting airplay wasn’t always necessarily the strongest material on a particular album.

“Most of the time what the record companies did back then is they they'd leave the best single on the album because they wanted you to go buy the album,” Mack told TheHistoryMakers.org. "They didn't make any money when you'd go buy the 45 or the 12-inch. And so they'd leave the best song on there. And I was always trying to find that best song.”

Los Angeles was a virtual dead zone for Hip-Hop music besides KGFJ (AM 1230) — who regularly broadcasted live feeds and mixes by Uncle Jamm’s Army — and KDAY 1580-AM, a station located on a hilltop at 1700 North Alvarado near Dodger Stadium.. Mack moved to Los Angeles in 1983. He sheepishly figured that even if things didn't work out, he'd make more in half a year in Los Angeles, than he was making for a full year in Houston.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

"I'm gonna take over this city."

- Greg Mack to StreetTV

Started in 1956, KDAY's moniker likely derived from its strictly daytime broadcast license. In its early days, it featured Top 40 music, well-known jocks like Art Laboe and Alan Freed, and comedians like Jack Burns and George Carlin. By the early 1970s, KDAY was broadcasting around the clock, and the legendary Wolfman Jack was on its airwaves.

KDAY jock, Steve Woods, played Sugarhill Gang's “Rapper's Delight” when it debuted in 1979. However, at one point, program director J.J. Johnson decided to scrub Hip-Hop from the playlist all together. According to Mack, KDAY was fifth in the ratings out of the five Black radio stations in Los Angeles at the time (KUTE, KGFJ, KJLH, and KACE).

It was clear to Mack that managers, Ed Kirby and Jack Patterson, were programming the station with an Urban Contemporary slant — mixing R&B, Wham, and Spandau Ballet — with the rare smattering of rap tracks from Run-DMC, Kurtis Blow, and The Sugarhill Gang. This, in his estimation, led to confusion for the listener.

“It was all over the place,” Mack told Urb Magazine. "But what was going on in the streets of LA back then was Hip-hop. At that time all the radio people in LA hated rap. Program Directors hated it, the big record stores wouldn’t carry it. They thought it was just a novelty and would go away in a year or so.”

Mack lobbied Kirby and Patterson to program more Hip-Hop. They eventually compromised; Mack could do whatever he wanted during the night shift.

A radio show’s success was measured by its Arbitron ratings — a system that measured the listing habits of people above 12-years-old between the times of 6 AM and Midnight. At the time of Mack’s hiring, KABC-FM was dethroned for the top spot by KIIS-FM after a 3.5 year reign. Together, the two dominated the entire market — with the other 40 local metropolitan stations accounting for less than 5 percent of the audience. Wally Clark, general manager and programmer for KIIS, attributed the success to a strong lineup of DJ’s and a popular format of top 40 pop music. Although KDAY wasn’t in the running for most popular radio station at the time, Mack’s commitment to playing Hip-Hop paid dividends almost immediately.

“The very first ninety days KDAY's numbers just jumped,” Mack said. “And they were like — you know, 'cause it was like at that time five black stations. We weren't competing with the whole market. We were just competing with the other black stations. KDAY went from number five to two immediately.”

While those listening were delighted by Mack’s devotion to Hip-Hop, both the record stores and labels were angry because KDAY was pushing artists who were afterthoughts in the marketplace. As a result, the mom and pop shops at swap meets like the Roadium became the main beneficiaries of KDAY’s night time strategy. Soon after, KDAY was amongst the first stations playing rap music during the day — strengthened by personalities like Russ Parr (who made good use of his rapping alter-ego, Bobby Jimmy), JJ Johnson, and Lisa Canning.

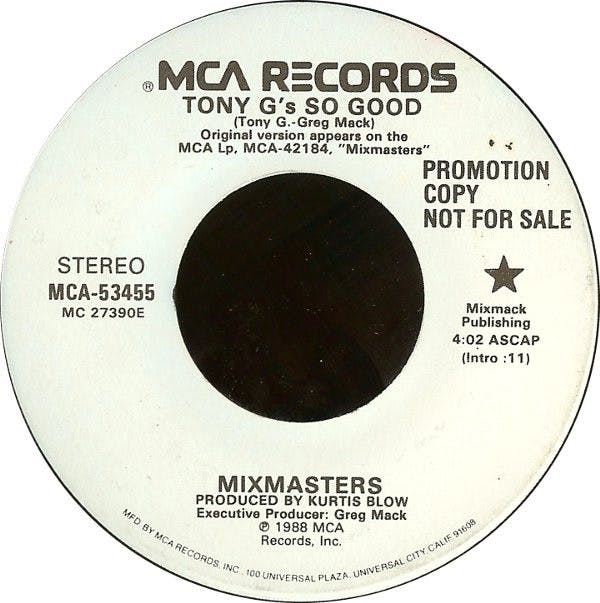

One of the most distinctive elements of KDAY was their in-house DJ crew called “The Mixmasters.” They spun records on location at places like Skateland, and then broadcast the feed live through a special phone line. Among the first and most notable members were Dr. Dre and DJ Yella of the World Class Wreckin’ Cru.

Rather than simply spinning records, Dr. Dre would splice different elements of songs together with a four-track mixer. A listener might hear “Oh Sheila” by Ready for the World, but the vocals would be a Prince song, and the harmony might be a different artist.

“Dre’s mixes became so popular and he was making so much money pressing them up and selling them at the swap meets, that he quickly got too busy,” Mack explained. “A year later he couldn’t do the mixes for us. So we recruited more guys.”

The next Mixmasters, Jammin’ Gemini and Tony G., were perhaps the station’s most important. Tony G — who moonlighted between KDAY and his heavy metal band Warlock — was referred to as, “the Kool Herc of the West Coast.”

“I didn’t really even have much interest in being a DJ back then,” Tony G said. “And I didn’t even listen to KDAY before I was on it, because I could barely get it in where I lived in El Monte. I really just got into it to make extra money on weekends. I did a lot of tricks at the time on turntables, and there weren’t many people in LA doing that kind of stuff. So it caught on.”

During Tony G’s five year tenure at KDAY (between 1984-1989), The Mixmasters would include notable DJ’S of the era like Julio G, Joe Cooley, M-Walk, Aladdin, Battlecat, Ralph M, Henry G (Hen-Gee), DJ Romeo, TraySki, and The Mixstress.

“From 1986 to 1989, we could do no wrong."

- Greg Mack

The on-location mixes were a hit. Shows like Friday Night Live — which aired Friday from 10 PM-1 AM — and Mac Attack Mix Master on Saturday from 8PM-11PM helped earn KDAY the largest teen audience in town. However, the live venues where they took place often became sources for violence. Tony G would attend his gigs with a dozen of his biggest friends and stored a sawed-off shotgun inside the walls of his speakers. Other people desperate to get their music on KDAY would offer cocaine, heroin, and handfuls of $100 bills.

In the late '80s, the station’s signal beamed out of six towers on a hill between Silver Lake and Echo Park. Their neighbors witnessed firsthand how prominent KDAY signals had become.

“It's awful, it's unbelievable, at night it's unbearable,” Silver Lake resident Tanya Busko told The Los Angeles Times in 1989. “You can walk in my yard when it rains and hear the 'rap, rap, rap' music on the chain-link fence. … In the bathroom, you can hear it coming through the toilet plumbing.”

According to Jheryl Busby, head of black music at MCA Records, KDAY successfully bridged the gap between the streets and the record company boardrooms. As much as the higher ups wanted to dismiss Hip-Hop completely, KDAY was proof of its longevity.

“And God bless KDAY, which has targeted that marketplace and shown that LA can be a very happening place,” Busby told The Los Angeles Times. “Without the radio exposure, the rap scene would have never happened so fast and now KDAY has gotten behind these groups. I think we’re really going to see this whole local scene come alive.”

Despite KDAY’s success, the station would go dark just as Hip-Hop was gaining new momentum in the ‘90s. At 1 PM PST on March 28, 1991, KDAY signed off the air for good. The 50-thousand watt signals on top of Alvarado St. would begin broadcasting for the “all business KBLA” at 1580 kilohertz on the AM dial.