One of rap’s early stylistic revolutions started with just a few words. At the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem in 1978, Kool Moe Dee saw Kidd Creole pass the mic to his brother Melle Mel while delivering a distinctive revved-up cadence that he slowed down toward the end: “Melle Mel, my flesh and blood is simply being the joint.

“That’s all he really said,” Kool Moe Dee says today. “But in that little moment of that cadence is where I was like, ‘Wow, that would be explosive if you kept that cadence going.’ My idea was to take that and start to use that as a style. I thought that would be like boxing and that would be like a flurry in a fight. I always related things to boxing, which is why the battle-MC thing made sense also. I saw life through a filter of boxing and I thought that doing that would be considered like a flurry.”

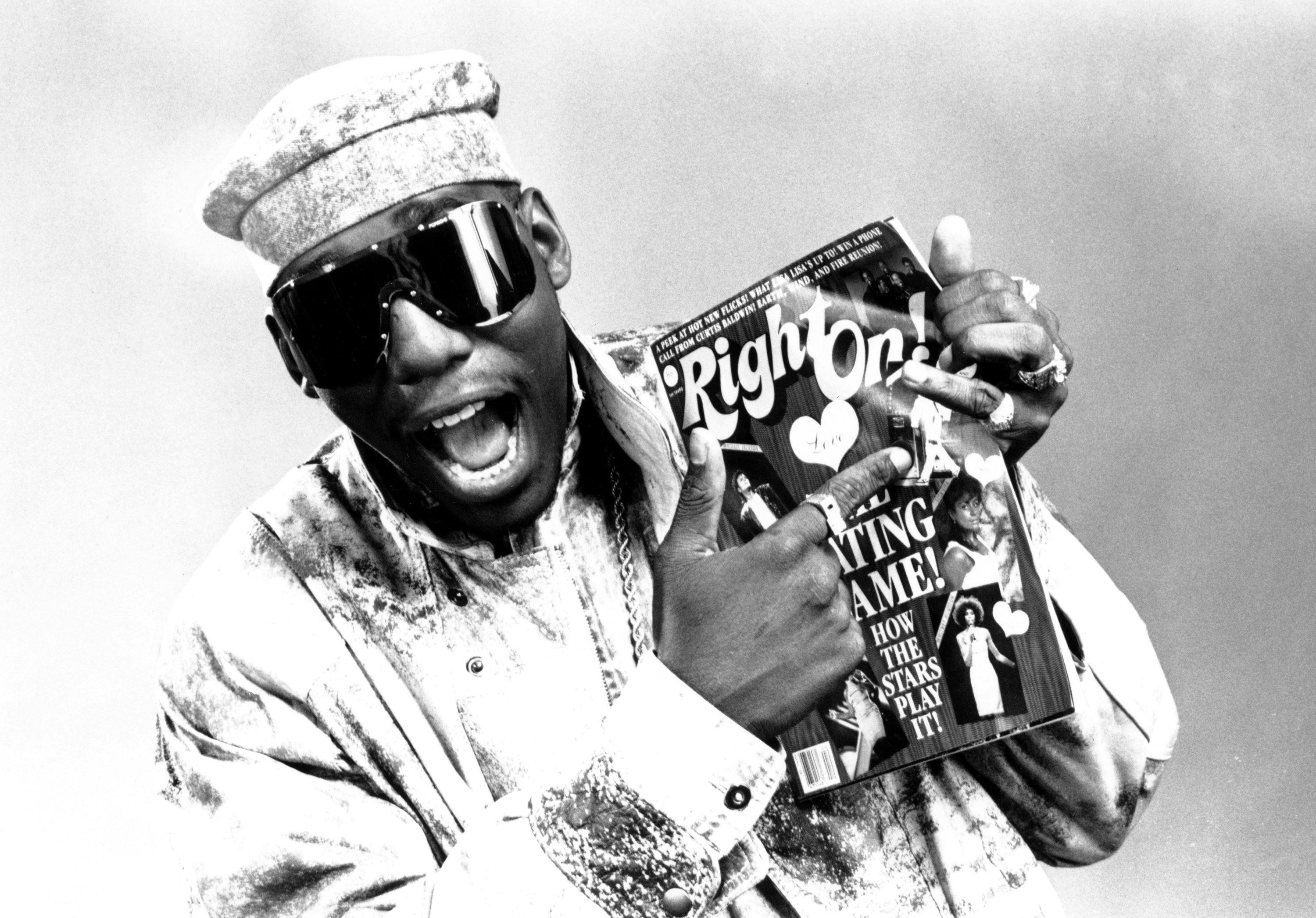

Kool Moe Dee poses with a copy of 'Right On' Magazine. The publication was first published in 1971. Credit: MICHAEL OCHS / WIRE IMAGES

Kool Moe Dee employed the style that soon became known as double-time rapping throughout his prestigious career, as did Big Daddy Kane. Kane had picked up stacking rhymes back-to-back from Grandmaster Caz and drew his inspiration from double-time from listening to Kool Moe Dee.

“Staying on beat but going rapid-fire,” Big Daddy Kane says today. “Moe Dee was the first person I’d seen do that.”

Moe Dee was excited about the style because he knew it would require several stages in order to master. “I understood instinctively that just saying a rhyme fast, you had to make sure that the syllables were in sync with each other in order for it to make sense, and a lot of guys don’t know how to do that to this day, quite frankly,” he says. “But when you’re doing rhymes in a different cadence and you’re double-timing the beat and sometimes triple-timing it, you have to make sure that the syllables syllabically make sense.”

Kool Moe Dee incorporated this delivery style into his seminal work with the Treacherous Three and as a solo artist.

Meanwhile, Big Daddy Kane honed his craft as a rapper, writer, and DJ, and he started working with an artist who was able to rap faster than anyone he’d ever heard.

“As far as that super-fast stuff, like what Twista developed into,” Big Daddy Kane says, “the first person I’d ever seen do that was Jaz-O.”

Big Daddy Kane, Jaz-O (going as the Jaz at the time), and the up-and-coming JAY-Z made a mixtape for Fresh Gordon, a producer-DJ-rapper who had featured the Jaz on his 1987 song “I Believe in Music.” Watching and learning from Jaz-O and JAY-Z inspired Big Daddy Kane to deploy the style in his own arsenal.

“One of the main things that used to fascinate people is that they would say, ‘Yo, you be going mad fast, but the crazy shit is that I can understand every single word,’” says Big Daddy Kane, whose rapid-fire rhymes on 1988’s “Raw (Remix),” “Set It Off,” and “Wrath of Kane” are among the best representations of the style to that point.

A year later, the man who became synonymous with rapid-fire rhymes was listening to LL COOL J’s Walking With a Panther album in Chicago. When Twista heard “Why Do You Think They Call It Dope?” he was floored. On the final verse, LL alternates between riding the beat and going at double and triple its tempo, something Twista had been focusing on too.

“The way I’m kickin’ the lines you can hear my tongue twist,” LL rhymes. “And it’ll have your neck spinnin’ like you’re spineless / I’m pickin’ ’em up, throwin’ ’em down / Hypin’ ’em up and slowin’ ’em down / All of these words with only one tongue / Shakin’ ’em up and then bakin’ ’em up.”

“He rapped fast in there and I was shocked,” Twista says today. “I was like, ‘Oh shit. Is somebody doing what the fuck I do?’ I couldn’t believe it.”

As Twista was soaking up LL COOL J, the Jaz was branching out, releasing his Word to the Jaz LP in 1989. The Brooklyn rapper enjoyed some success thanks to the comical love story “Hawaiian Sophie,” which featured him delivering rhymes in a mid-tempo flow that matched the song’s beat, something echoed by collaborator JAY-Z.

The following year, the Jaz released his second album, To Your Soul. The collection’s lead single, “The Originators,” featured the Jaz and JAY-Z rapping at breakneck speed throughout the entire song. Despite the skill both rappers displayed, “The Originators” did not become a massive hit, something that may have had little to do with the song itself and more to do with how rappers are perceived and received.

LL COOL J flashes a peace sign at a record release party for Run DMC's album "Tougher than Leather" at the Palladium on September 15, 1988 in New York City. Credit: CATHERINE MCGANN/GETTY IMAGES

By 1990, Kool Moe Dee, Big Daddy Kane, and LL COOL J had long established themselves as versatile MCs whose catalogs boasted a wide range of sounds, styles, and deliveries. So while they were respected for the wide-ranging and diverse delivery styles they routinely employed, other artists were not always afforded the same luxuries. Even though the Jaz was as versatile an artist as his commercially successful predecessors, most consumers at the time were only familiar with him through the lighthearted “Hawaiian Sophie,” which stood in stark contrast to “The Originators,” a lyrical and stylistic showcase. Artists typically get pigeonholed, and rappers are no exception.

“What happens with Hip-Hop, fortunately and unfortunately, is you get defined by who you are and what you do,” Kool Moe Dee says. “Once you get defined that way, it’s very hard for people to see you on another side. It would be like Chuck D making a gangster record. It doesn’t work because it’s Chuck D, not that the beat couldn’t be dope or the lyrics couldn’t be dope, but because it’s Chuck D. He’s already identified with pro-black and consciousness, so there’s no way he could do a gangster record. I think how you come in and how you’re defined really takes precedent in a lot of ways over what people think you’re doing.”

Even JAY-Z wasn’t exempt. He enjoyed his best-selling album with 1998’s quintuple-platinum Vol. 2… Hard Knock Life. One of the collection’s singles was “Nigga What, Nigga Who (Originator 99),” a nod to the Jaz’s 1990 single. The song even featured his mentor, who was going as Big Jaz at the time. Even though it was released as a single, was produced by Timbaland and had a video, the song wasn’t as successful as the project’s other singles “Hard Knock Life,” “Can I Get A…,” “Money, Cash, Hoes,” and “Money Ain’t a Thang.”

“You’ll find millions of people that can sing that hook,” Big Daddy Kane says of “Nigga What, Nigga Who.” “Ask them to spit some of JAY’s verse. The late ’80s on up to the late ’90s, it was just so lyrical. People wanted to hear what you’re talking about.”

Even though fans may not be able to recite the lyrical gymnastics of rapid-fire rhymers, the skill is now embraced by huge swaths of fans. Thanks to Twista, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, and others, the style is now celebrated, something that speaks to rap’s evolution and the evolution of its audience, which has become larger, more sophisticated, and more segmented over the years.

“If you’re just doing the marginal, simplistic levels of party, call-and-response, basic simple rhymes to keep the party going,” Kool Moe Dee says, “you’re not doing justice to what I would call the lyrical part of the hip-hop sandwich, the verbal part of the Hip-Hop sandwich.”

Thanks to a spark from Kidd Creole, hip-hop’s sandwich has several extra layers tied to double-time rhyme.

* Banner Image: Scrap Lover, Big Daddy Kane / Photo By Raymond Boyd/Getty Images