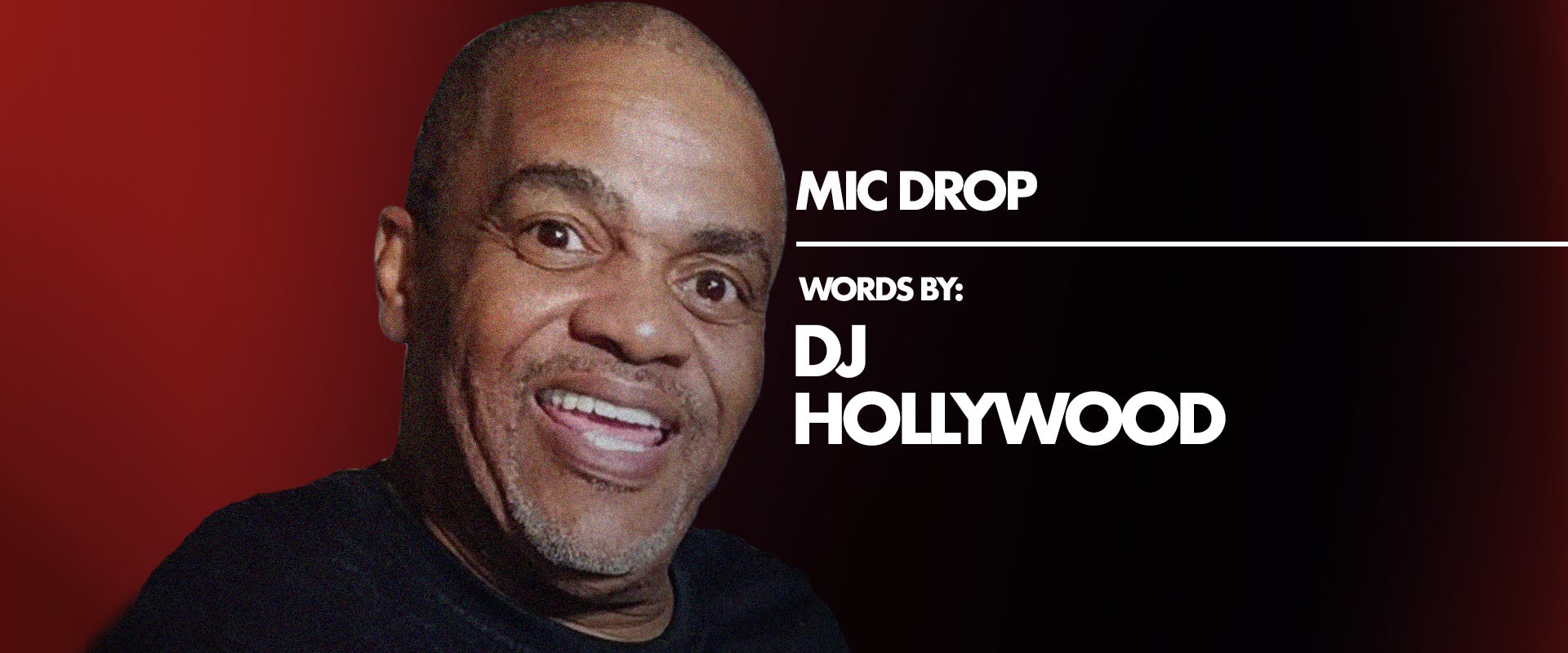

MIC DROP is a recurring series featuring the thoughts and opinions of some of the biggest voices in classic Hip-Hop. Raw, uncut — and in their own words — these are the gems you've always wanted.

My parents weren't together, so I was really raised with my mom. My first few years of going to school — grades one to three — I did in Philadelphia with my grandmother. Then I came to Harlem in the third grade. By the time I was 14, my mother and I didn't see eye to eye on a lot of things, so I left. I was on my own since 14.

That was really rough, but I brought it on myself. My mother was like, "If you can't do what I say do, then you need to get out." I didn't feel like I wanedt to do what she was telling me to do. I guess when you're young, you think you know everything, and you really don't know diddly. But, living by your word, you kind of put yourself in a position and you can't back down once you go. That was really stupid.

I slept in the basement. In the summertime — when it was hot — I slept on the roof. I made it work. I wound up working in after hour spots where I got to know all the hustlers. At eight o'clock in the morning in New York you get a ticket, and everybody mainly in this spot was double parked. So I would go outside and move the car from one side of the street to the other side. I used to drive Cadillac's and all kind of cars when I was 14.

Even sometimes a guy would say, "Yo man, I left my car on 127th street, go get it." And we are on 132nd, so the cars are on 122nd and 8th, and we on 132nd and 11th. Now, I'm driving that far with no license. No sir, every day I'm taking a chance of not only getting myself messed up. After hindsight, you understand, after looking at it from another view, what was I picking up in a car on 122nd street and bringing it back? But, after aging a bit and knowing what people do, I could have been pulling guns or pulling drugs, anything.

It's 1971. I'm making $15 a night. And I got privileges — like cocaine — and all that type of stuff.

I'm privileged to be able to do what the big boys do. At the end of the day though, that turned out to be the worst thing in my life. The drugs took all the money that I made.

In New York there was a station called WWRL. Every week they had a pamphlet that came out with the hits of the week called "The Big 16." Checking "The Big 16" was it. My mother used to have card games from Friday to Sunday. On Saturday when I got up, she's cooking and she's doing this and that and the other. She told me, "Go on and put some records on." Because she didn't have time. So I'd go put records on. I don't know what records I'm putting on, I'm just putting the records on. I watched people popping their fingers. Then all of a sudden a record would come on and everybody would be like, "Oh." So that was a record that my mother would say, "Boy, why do you put that on?"

I don't know why I put it on, I just put it on. But then I started to develop taste. I kind of knew the records not to put on. I would be so happy with myself because I could keep things going — keep people on a happy side. I didn't know that that I was going to be a DJ, but it sure gave me good taste and great knowledge in music.

I was working on a mic mixer. It wasn't a mixer made for doing turntables. I had no headphones, no nothing. So I had to guess my way into putting a record on by trying to find the timing. I devised a way I could turn up the other turntable while while the record was playing and try to find that first beat — or that first notch of the record — so I could just bump it right in. You could clearly hear that record, but if you're drinking and you doing what you doing, you ain't paying that no mind.

I mostly played R&B and Soul music. Soul music was the key to my whole existence really. I knew white records, but I didn't know them like I knew Soul records.

I was traveling with the number man. We went to this bar up on Sugar Hill and he said, "Yo, go sit over there." We'd be at this spot for two hours — moving his numbers in — and doing his little coke thing.

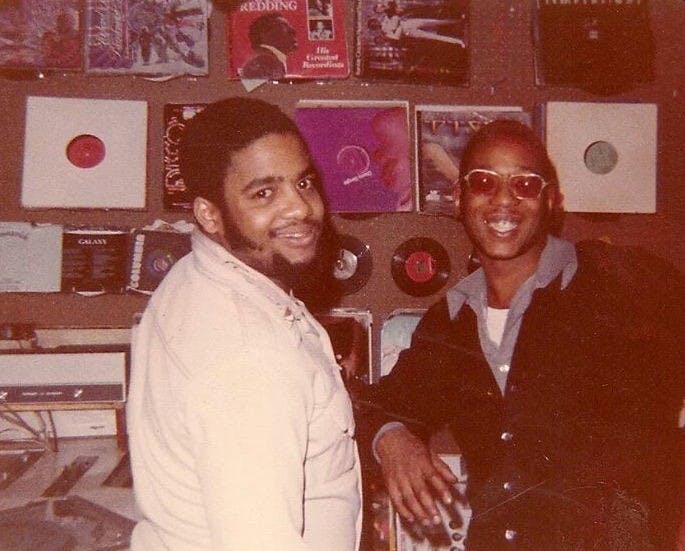

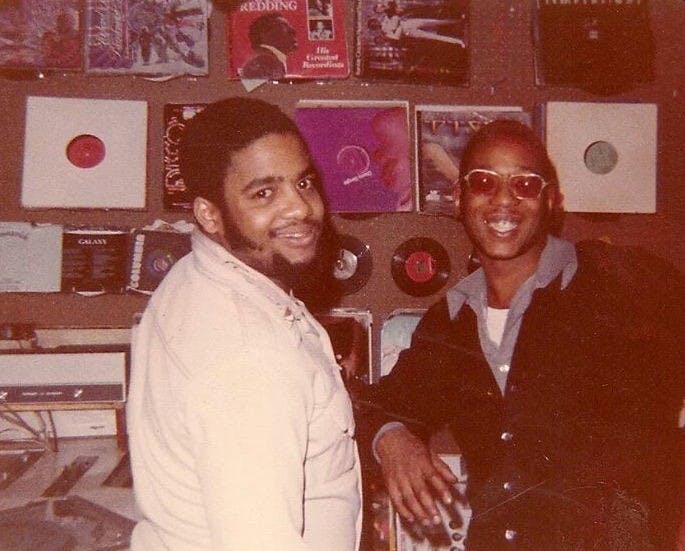

They had a DJ named Duke in there who was only using one turntable. One day something happened at Duke's house and he had to go. He said, "Now I know you've been watching me, I know you know what to do. Go ahead, just do this until I get back."

He should have never did that. I was like, "Oh wow." So now I'm sitting here, I'm playing the records, and while I'm taking a record off to put the next record on, there's silence. There's nothing. So I began to talk.

"Hey listen, right now we going to do what we do, the fun stuff. Hope you've had something good to eat." All the while I'm changing the record.

After a while, my conversation started to get a little better. As a kid in Harlem, there was talent shows everywhere, and we used to go to talent shows. I finally got in a group called the Innovations. I used to sit on 133rd street on a stoop and rehearse. All the girls double ditching would come over there to hear us croon.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

"Hollywood" was always my name because I could dance.

I used to rip dancers and dance groups down. I stopped hanging with the numbers man — everything just went out the window. All I wanted to do was play this music. I'd help Duke when he wanted to take a break at places like on 148th and 7th Avenue in the basement.I became the primary player. I wasn't going to school. I wasn't doing nothing. This was all I thought about. I was working in the after hour spot six days a week in 1971.

It was so magical making these records jump. The things I would say, people would respond to it.

I came up with the formula that while I'm doing DJing, I was going to make people speak back to me. At that time, DJs didn't talk. That's how throw your hands in the air and all that stuff just came into play.

I'm able to read crowds. If you can't read crowds, this is really not the game for you. There's a lot of dudes that can't read for shit, but they got the job. You learn the mechanics.

When I was on the microphone and doing my thing, the people in the crowd were like, "Yo man, can somebody tell this guy to shut up and let the goddam record play?!" Because they weren't ready for that. It's just like breaking a record.

That sense of riding the rhythm was just real easy to do. What I guess you would call an "MC," that is an announcer to me. When so-called "Hip-Hop" started in '73, that was something I'd been doing for years. All they did was take my style and change the name. You're like Christopher Columbus — you're coming in and you're discovering something — that's already fucking here. If Kool Herc is the beginning of what this is, then you got to look at him like Thomas Edison. Because if he started it, I'm the one who put in the filament so the light would stay on.