Classic Albums: 'Licensed To Ill' by Beastie Boys

Classic Albums: 'Licensed To Ill' by Beastie Boys

Published Mon, November 15, 2021 at 12:00 PM EST

None of you look like I would pick you for success..."

- Joan Rivers interviewing Beastie Boys, 1987

In 1986, the Beastie Boys—a white rap group comprised of three Jewish guys from Brooklyn—crash landed into pop culture with their multiplatinum debut, Licensed To Ill. The Rick Rubin-produced album helped cement Def Jam Recordings as rap's biggest label, Rubin as it's most famous producer and the Beasties as Hip-Hop's newest, whitest, and most controversial phenomenon.

Michael Diamond and Adam Yauch were punk rock friends from Brooklyn Heights, who'd meet up with the slightly younger Adam Horovitz, and played in hardcore bands supporting acts like Bad Brains and Black Flag before making the switch to rap music after hearing rap groups like the Funky Four+One. Making their rap debut with the single "Cooky Puss," (based on a prank call to Carvel Ice Cream), the Beastie Boys caught the attention of burgeoning producer Rick Rubin. Rubin was in the midst of launching a rap label called Def Jam, and he introduced the group to Def Jam co-founder, Russell Simmons. Both Rubin and Simmons were convinced of the commercial potential of the group; and soon the Beastie Boys were signed to Def Jam, with the label pushing what was to become rap's first major white act.

They'd only been rapping for about a year.

"I think it was weird, but it just didn't cross our minds that it was weird," MIke D reflected to NPR in 2018. "We just loved hip-hop. I think when we started to make rap music...when we made our first record with Rick, which was not very good: 'Rock Hard;' I mean, really, I'm doing myself a disservice by even mentioning it. The first time that we went up, we played a show and at the Encore—opening up for Kurtis Blow—the Encore in Queens. We were so excited, we all were in Puma suits and fucking durags. And we go and people at Encore are looking at us like... I don't understand how we did not get killed that night. I really don't. Because if I were in the audience, I would have killed us."

Ad-Rock, MCA and Mike D soon figured out that they would do better for themselves not pandering or posing; as they adopted a more screwball, crazy-white-guys image. With Rubin as the musical mentor for their most demented song ideas, the trio set to work on a debut album that mixed irreverent humor, an affinity for classic rock and a love for the early call-and-response style of pioneering rap crews. Rubin was already riding high on the success of LL COOL J's 1985 album Radio, and he'd produced Run-D.M.C.'s smash Raising Hell. With the Beasties, he got to go even farther out, melding samples and crafting songs that took as many twists and turns as these wacky rap personalities could muster.

Then there was the Madonna tour.

DROP YOUR EMAIL

TO STAY IN THE KNOW

While still working on the Beasties' debut album, Simmons got a call from Madonna’s manager, asking if the Beastie Boys would be interested in opening on her Like A Virgin tour. Beastie Boys would be going on the road with The Material Girl herself; and Madonna's mallrat audiences were ill-prepared for the chaos of Ad-Rock, Mike D and MCA.

"Oh, it seemed like, you know, America," Mike Diamond said in 2020. "Like, we left New York—that was noticeable. That we had left the city. We’d be in, you know, no offense to wherever, but we were in Dallas and we were, like, 'Whoa, this is not New York City.' Everything else seemed quaint and small-town, you know?"

Madonna's fans hated these loudmouth rappers, and on most nights the feeling was mutual. The Beasties actively provoked the audience and one Madison Square Garden show was particularly hostile, as the audience booed the Beasties for virtually their entire set. After a show at Seattle's Paramount Theater, Ad Rock joked that “Me and the boys are gonna go backstage and tell Madonna what a great audience you are." Madonna was suddenly making the leap from theaters to arenas, and her management wanted to drop the Beasties following the bad crowd receptions. It was Madonna herself who fought to keep them on the tour.

Their notoriety was at all time high, even as the Beastie Boys had yet to deliver an album. "Hold It Now, Hit It" was released in spring 1986, a sample-driven collage of hardcore boom-bap. The song was born of the Beasties love of tinkering and Rick Rubin's production magic, and it announced the Beastie Boys formally to the world. It was but a sample of what was happening on Licensed To Ill.

"Rhymin' And Stealin'" featured the group's obnoxiously over-the-top rhymes against a backdrop of Led Zeppelin's thunderous "When the Levees Break," and "The New Style" would become something of a harbinger for where the Beasties would go in years to come: fully irreverent, oddly influential (Ad Rock's famous "Mmmmmm...drop!" declaration has been endlessly sampled) and "Girls" represents the kind of frat boy misogyny that would become a trademark of the Beasties 1980s image. "Brass Monkey" became a college party anthem, an ode to cheap liquor and wildin' the fuck out; as "Paul Revere" was notable for the violent gunplay in the lyrics and the song's innovative "backmasking" production. This was a group as much invested in anarchist punk tropes as hip-hop style; both come across on their first album.

Licensed To Ill dropped like a bomb on American popular culture. With Hip-Hop making it's first major mainstream inroads, ...Ill was the right album for the times; a rap album that was ready-made for middle American rock fans. The Beastie Boys were suddenly selling records to an audience who'd never heard of the Latin Quarter or Melle Mel; metal and heartland rock fans who just needed a loud, obnoxious soundtrack for a loud, obnoxious Saturday night. And in the beginning, the Beasties were certainly happy to oblige.

They were suddenly the most talked-about new act in music.

The Beasties became infamous for performing with girls in cages and an inflatable penis on stage, while spraying beer onto the just-as-boorish audience. They were banned in the U.K. for lewdness.

The group made an appearance on The Joan Rivers Show in 1987, and Rivers laid into the trio, kicking things off by asking "How'd you three all get together? Juilliard?" The Beasties were in rare form and so was the host.

"How are your parents taking all of this because it must because it must be incredible for them to think ‘Here’s a kid who sat around the house and threw ice cubes’ …None of you look like I would pick you for success. No offense …your parents must be six of the happiest people in the world, because it was this or Leavenworth. …I’m trying to find out how your parents are taking this…"

Run-D.M.C. had dropped Hip-Hop's first multiplatinum blockbuster not even six months earlier. Raising Hell was a rap game landmark; "My Adidas" was a hit in spring of 1986, but it was "Walk This Way" the album's rock-centric, Aerosmith-paired second single that sent ...Hell into the stratosphere. With LL COOL J's Radio setting Def Jam's commercial bar and the gargantuan success of Raising Hell, the table was set for Licensed To Ill to be huge. And of course, the whiteness of the Beastie Boys had its commercial pluses and cultural minuses.

But perhaps no song came to embody the early Beastie Boys like the fourth single from Licensed To Ill. "Fight For Your Right" was intended to be a satire of the kind of suburban cock rock that had taken over MTV. Songs like "We're Not Gonna Take It" by Twisted Sister and "Cum On Feel the Noize" by Quiet Riot were music video staples, and the Beasties sought to poke fun at that kind of mindless headbanging with an anthem all their own. "Fight For Your Right" became one of the most popular songs of the decade, shooting all the way to the Top Ten of Billboard's Hot 100.

“It wasn’t until “Fight for Your Right (to Party)” came out that we started acting like drunken fools," MCA said in an interview with Tikkun. "At that point, our image shifted in a different direction, maybe turning off the kids that were strictly into hip-hop. It started off as a goof on that college mentality, but then we ended up personifying it.”

Because of the group's image, and its undeniable commercial success, the legacy of Licensed To Ill is inextricably tied to the ongoing conversation surrounding white privilege and popular music. The spraying beer cans and gonzo cartoonishness of the group's mid-80s breakthrough lent itself to criticism: here were three white guys selling big records making rap music that, in many ways, made a mockery of rap music. It wasn't intended to be a parody of Hip-Hop, per se, but it didn't endear the Beasties to folks who believed they were culture thieves trading on the lowest common denominator.

It should be noted that the three Beasties themselves were and have always been reverential to the rap music that inspired them and to the artists they came up alongside. But the image they'd crafted was swiftly becoming a proverbial albatross; even with Licensed To Ill's blockbuster success, it was apparent that something was going to have to give. And they started to believe that Simmons only saw them as a one-trick pony.

“Russell was like, if you don’t go in the studio, then I’m not paying you. But we were all immediately, ‘Fuck you.’”

- Mike D on the Beastie's feud with Def Jam

Now, the Beastie Boys were the biggest thing in rap. They were taken in as compadres by the other Rush Associated acts under Simmons' umbrella; which included Run-D.M.C. and Public Enemy. Their success was proving to be a double edged sword; America's favorite white rappers were starting to chafe at the idea that they were just a frat boy novelty act.

The Licensed To Ill Tour became a turning point for the Beasties in unexpected ways. The grind of touring and the frustration with playing up their "wild party guys" image began to wear on Yauch, in particular. The beer-slinging hijinks made Beastie Boys look like a joke and MCA was burnt out on the cartoonishness. Further complicating things was a deteriorating relationship with Def Jam, Simmons and Rubin. The label was demanding the Beasties deliver a follow-up to ...Ill. But the group was furious to learn they weren't going to be paid until/unless they delivered their second album.

“Russell was like, if you don’t go in the studio, then I’m not paying you,” Mike D explained to NME years later. “His calculation was that we would all be like, ‘Oh we want our millions. OK, Russell we’re going to do it.’ But we were all immediately, ‘Fuck you.’”

The third strike was the group bristling at the notion that they were purely a creation of Rubin's genius. Rick Rubin had shepherded Licensed To Ill, but the Beastie Boys weren't interested in a svengali. Success seemed to be the worst thing that could've happened to the relationship between the label and the Beasties.

"Eventually it turned into a money thing," Rubin shared in 1995. "But I think it started more from [my] getting credit for the music, and people making them look like they were my puppets."

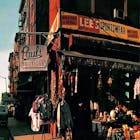

A testament to it's middle American appeal, Licensed To Ill is still the best-selling rap album of the 1980s. But the Beastie Boys spent years attempting to extract themselves from its success. They'd fight their way off of Def Jam and disassociate from Rubin and Simmons; eventually landing on Capitol in Los Angeles and reinventing themselves as alt-rap auteurs on 1989's Paul's Boutique and into the 1990s, with acclaimed, genre-pushing albums like Check Your Head and Ill Communication. They would also spend years apologizing for the misogyny and homophobia they embraced during the wild Licensed To Ill era. The Beastie Boys matured and evolved; but Licensed To Ill is still a huge part of the group's legacy. For better or worse, it stands as a snapshot of how complex the intersections of music and race can be; and how self-awareness can help a lot of artists navigate the tricky curves.